I love adorable cats. We love persuasive video games. And we especially love when the two of us clash with a wealth of experiences of mature stories that pull on the strings of our hearts and remind us how deeply our cat friends love us (with engaging emotional consequences).

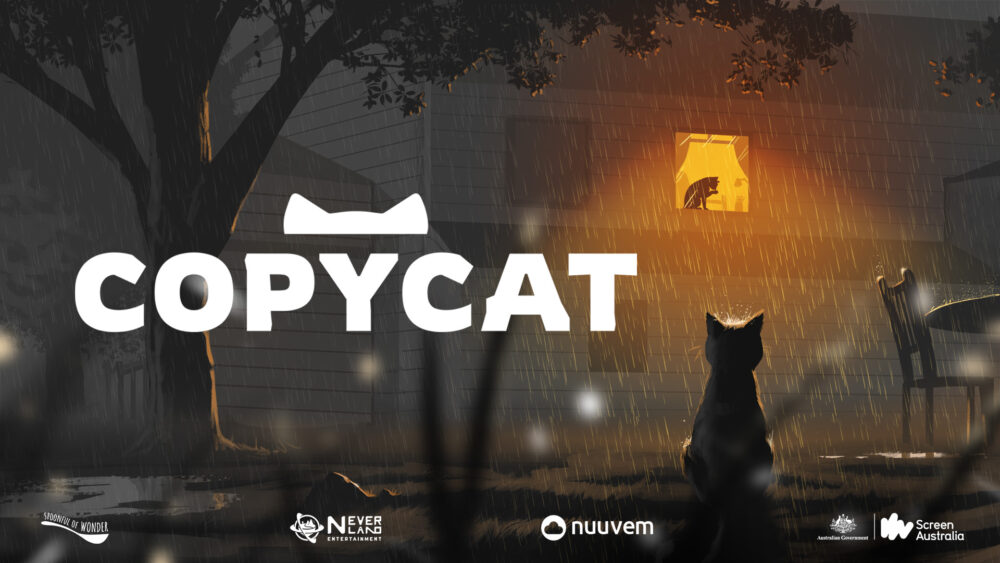

Developed with support from Screen Australia, Copycat is the debut title of developer Spoonfun of Wonder, led by writer Samantha Cable and director Kostia Liakhov. A story-driven video game that explores the highs and lows of family, homes, and abandonment for both humans and kittens.

Released for Steam on both PC and MAC in September 2024, Copycat is poised to release cute feet quickly on the PlayStation 5 & Xbox Series X/s. Prior to the release of the PS5/Xbox, we had the opportunity to speak to the founders of Samantha Cable, author, story director and founder of Spoonful’s Wonder of Wonder.

What inspired the concept of Copycat? Also, how did you translate that idea into a full-fledged game?

Samantha Cable (SC): Copycat explores deep love for pets using a story-driven video game medium. This special bond we share with cats (and dogs) is different from other relationships. Pets love us on good and bad days. Through fun and tough times. Cats in particular have played a major role in my life. However, the systematic issues of pet abandonment weigh heavily on my mind.

As living costs rise and more people abandon their pets, animal shelters are now capable. Therefore, I was inspired to write a script that demonstrates the complex and subtle world of cat ownership. Copycats are about pets who learn to deal with abandonment and humans who are forced to surrender. Together, the two souls set out on a journey to discover the meaning of their family and home. Cats were the perfect container to tell this story. I wanted players to walk on the paws of their newly adopted cats and experience the fear of adapting to their new home. All these themes came together to create our first game, “Copycat.”

Why do you believe that sadness is an effective tool for game developers? Can this be shared a specific moment with a copycat that was intentionally used?

SC: Sadness and melancholy have always been an important part of the human experience. Even in ancient Greek times, we had tragedy that balances comedy. Sadness aims to emotionally move the audience. Sadness and catharsis can provide depth, especially in the case of games. But they don’t have to be always negative experiences. For example, seeing the hero achieve something he can’t do before can make him emotional. We can be proud of them. You can feel the heartfelt sensation and heart ache. Without sadness, the highs are not so profound and grand.

This is a real, well-balanced act for game developers. A particular example of imitation occurs at the second turning point. It required an emotional beat that linked the player to Dawn (the main character of the cat) and felt that what was left was really left behind. I used my grief to pivot into Act 3, giving players the opportunity to reflect on the ethics of pet ownership. This tool meant that it could carry an emotional sloop line of the story and attract players.

Can we let us walk the process of creating particularly emotional scenes of copycats? What factors contributed most to that impact?

SC: Copycat has many emotional scenes. Some felt fulfilled, while others felt euphoric. Some felt empty, while others felt sentimental. Each scene was carefully created to resonate emotionally with the player. Each moment began with a strong story and theme, but there are many other tools that developers can use when creating emotional scenes. Let’s explore the director’s tools first. Directors can use color theory to help with the atmosphere of the scene. In Copycat, cool colors such as blue and grey are associated with abandonment and homeless emotions.

This is compared to previous scenes in the game, filled with warm red and orange to symbolize safety and love. The camera is another great supervision tool. When you want the player to be small and overwhelmed, place the camera far away from the hero. Or, especially in intimate scenes, swap the camera for a character’s POV. This really helps players to be in our hero’s shoes (or feet).

Music is another great tool for developers when creating emotional scenes. We have been conditioned as humans to associate different emotions with different instruments. Therefore, it is important to be intentional in the selection of equipment. You can also use LeitMotifs to assign different melodies to different characters. It gives the player a certain sense. So, revisiting this melody later will remind you of this feeling. In our experience, the story, direction and music work to harmonize and create emotional scenes.

In your opinion, why do you have so many sad moments that last a long time since the console is turned off? What do you want players to take away from these experiences?

SC: Games have the power to get deeper into players. As a result, sad moments remain. The first reason (and one of the most powerful) is because the player physically experienced a sad moment. The interactive nature of video games goes beyond classic storytelling, as players are not merely passive observers (theatre, film, television, etc.). The player is a character. In other words, they are the ones who make tough choices. They are the ones who win and lose. They are the ones who break their hearts. None of the existing media has such power, making our game for cathartic recharged stories an incredible container.

Secondly, sad moments stay with us. Because we have time to look back on them. Most games are designed as a longer experience. In the indie world, players usually expect 6-10 hours of stories for smaller projects, but in AAA titles it can take 30-50 hours to reach the credits. For some games, it takes 300 hours to complete. Due to the period, players will have more time to develop relationships with their characters, stories and worlds. Also, between play sessions, you must look back at the sad moments the players have had up until now. Ultimately, players are also left with a new sense of mental clarity, allowing them to freely reflect on the deeper meaning of the story.

How does the game create a safe space for players to handle complex themes such as sadness and loss?

SC: Catharsis acts as a safety valve and allows for the elimination of pent-up emotions such as stress, anger and sadness. It provides a healthy outlet for viewer representation and a safe space to handle complex themes such as sadness and loss. Compared to movies and theatres, the game gives players unique flexibility and freedom of choice. In many cases, you are free to explore themes at your own pace.

This makes it more accessible to a variety of players and allows them to pace themselves when running difficult topics. Often, players can take a step back on in-game side activities once they are ready to embark on a new chapter in the main story. Most games are intended to be experienced in multiple sessions by design, like books.

What practical tips would you offer aspiring authors and developers looking to incorporate catharsis into your game?

SC: Take care of the players and beware of their limits. The game is a relatively new storytelling medium. As long as there are many incredible examples of beautiful and moving cathartic stories available, the game is still widely associated with “fun”, “action”, “conquest”. For this reason, players have different limitations when it comes to heavy stories and need to respect that. We need to take care of the players and realize that after a long day, there is something there to relax and become a cat without breaking your mind.

This also extends to how the story is arranged. It’s important not to mislead the players and make sure they know what they’re experiencing. To avoid false expectations, always consider trigger warnings and create game descriptions and marketing materials accordingly.

Finally, aspiring developers are encouraged to focus on the quality of the game’s redemption. At the end of the day, due to the interactive nature of the game, they still rely heavily on players winning. For example, you can defeat the final boss, complete the hero journey, or close it in another way. If players feel that they have “lost” the game, it may leave them with a bitter aftertaste or potentially reflect the overall reception of the game.

We did the best work we could with Copycat, but looking back, there’s a lot to do to improve. Imitation is far from perfect.

Are there any personal connections to the themes explored in Copycat? How did that have an impact on your storytelling?

SC: What a wonderful question. Since Covid, Costia and I have been working remotely and have been bringing the spaces to light while working on the game. Although this experience is very liberating and sometimes lonely, I recognize that the definition of attribution and home are very different from most. Growing up, my family has moved homes between New Zealand and Australia many times. So it was as if I lived in the middle and never belonged to either place.

On the other hand, Kostia has a different relationship with the theme. Kostia cannot return home due to the war in Ukraine. His parents have been evacuated and have not returned to their town in almost two years. We both have a nuanced relationship with the meaning of home and belonging. So it makes sense that we were attracted to it as a theme.

We want to remind players that the home is not certain or guaranteed. A home is not always about things, places, or people. This is because not all three of these things are always possible. Instead, a home is a sacred space that evolves and changes over time. The house can be broken and repaired. The house can be found abandoned. But most importantly, the home is where you need it most. These themes of belonging meant something big for us, and we wanted to give players the opportunity to reflect on it for themselves and a quiet space.

What are your favorite emotional moments in other games that have influenced the copycat job?

SC: Over the past few years I have had the opportunity to enjoy dozens of incredible story-driven games that have made me laugh, cry, think, and reflect. Many of them shaped me as a story designer. If I choose a few, I would probably scream the next masterpiece:

Life Is Strange (Nod Nod, 2015), allows you to make impossible choices for its beautiful storytelling and ultimate heartbreak. In my opinion, character buildings, music and plots are masterclasses in storytelling. The Brothers: The Story of Two Sons (Starbreeze Studios, 2013) is a story about how they exploited the user experience and the control scheme of the game to provide cathartic experiences in new and unexpected ways. Florence (Mountains, 2018) relied on visual metaphor, nostalgia and pacing to tell stories and express the emotions of characters through very simple mechanisms.

Copycat will be released on May 29, 2025 on PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X | S. It is currently available on PC via Steam and MacOS.